The current public school pension system is fiscally unsustainable in many states, contributing to depressed wages and presenting a major threat to school budgets (despite only benefiting a minority of teachers in the workforce today). Let's talk about the +$600 billion budget cut happening to public schools.

The hidden +$600 billion cut to ed budgets this decade

The $190 billion ESSER stimulus figure has been making headlines since the passage of the American Rescue Act in March 2021—it’s a big number that’s turning heads about its potential impact on K-12 education. Over the same six fiscal years that the ESSER grants are eligible for spending, public education will pay nearly $300 billion in teacher pension debt payments.

You read that correctly: that big $190 billion number that everyone can’t stop talking about won’t even cover unfunded teacher pension liabilities over the same period of time. If the trend continues (which seems likely based on recent economic performance), the public education system will be on the hook for at least another $300 billion through 2030. This money comes out of school district budgets—so why is no one talking about the +$600 billion budget cut that is happening to public schools this decade?

Figure 1. Retirement systems for teachers are assuming their payroll grows at 2.9% over the next decade, and whether using that rate or a more conservative 2% payroll growth level, projected pension debt payment between 2020 and 2030 are between $605b and $635b.

Let’s put this into perspective: imagine you have an $800 balance on your credit card and you pay $50 each month while interest is compounding. Your minimum payment will quickly increase as your overall debt balloons. Now, add nine more zeros—this is the budget-crushing challenge of our teacher pension system. The debt payment is ticking up to $50 billion per year and growing, while barely making a dent against the total $815 billion liability.

For comparison, total ESSER spending across the 4.5 year grant period would average only $42 billion per year. If there is such pearl-clutching scrutiny about ESSER spending, why isn’t there equivalent outrage about $40-50 billion per year coming out of education budgets to pay down pension debt?

Most teachers are not served well by their pension plans

Aren’t pensions a good thing? Isn’t a pension plan one of the biggest perks of a career in public service? This is a classic case of several things being true at the same time:

- Pensions are an incredible benefit for most career teachers (+20 years of service) who account for an increasingly small proportion of teachers.

- Unfunded pension liabilities are crushing school budgets.

There is only one group served well by all retirement plan types on average: teachers who work their full career and leave when they reach retirement eligibility. However, only 8-15% of teachers hired today are expected to make it to retirement age with full benefits, depending on the state’s eligibility requirements for years of service and age of retirement.*

* And even then, some teacher pension plans don't offer inflation adjustment of pensions, which makes these pensions less secure forms of income in the long-term.

We are in dire need of candid, collaborative conversations about how to improve the funding and benefit offerings of teacher retirement systems. It seems that we collectively avoid this conversation because even broaching the topic of “pension reform” can be construed as being "anti-teacher."

You know what’s anti-teacher? Keeping teacher salaries flat for decades, maintaining a system that benefits the few at the expense of many, and risking the very solvency of public education— that is anti-teacher. The trend of pension debt as an increasing proportion of public school spending is not fiscally sustainable. We need to cut through the moralizing and have some hard conversations.

What we can learn from the numbers

In the decade between fiscal years 2009 and 2019 (adjusting all figures for inflation):

- K-12 education spending increased 9%

- Total pension spending increased 90%

- Pension debt payments increased 240%

The rising cost of pension debt is taking up an increasing proportion of education budgets, which makes it harder to increase teacher salaries or any other budget line-items.

Figure 2. Total pension debt payments are on the rise, increasing at a much faster rate than pension contributions or K-12 education spending at large. (Source: Equable)

Figure 3. Over the past decade, pension debt payments have accounted for a greater and steadily increasing percentage of annual K-12 spending compared to pension contributions. (Source: Equable)

The Underfunded States of America

Pension reform is one of the trickiest topics to navigate in the world of education finance because the percentage and amount of unfunded pension liabilities varies wildly from one state to the next.

Figure 4. The amount of unfunded pension liabilities varies drastically by state. (Source: Equable)

The funded ratios of public school pension plans by state ranges from 37% (New Jersey) to 110% (Tennessee). California* holds the single largest amount of unfunded liabilities at $110 billion, even though it is 78% funded.

* Recall that Governor Newsom boasted a $97.5 billion “surplus” in 2022 despite $275 billion in unfunded liabilities across all California pension plans.

Figure 5. The funded ratios of public school pension plans varies across the nation, from 37% funded in New Jersey to 110% funded in Tennessee (and everywhere in between). (Source: Equable)

The wide variance in how well-funded state pension systems are is matched by the variance in the impact on K-12 budgets.

Some states have steadily increased K-12 funding at equal or greater rates than the growth rate of retirement costs. As a result, annual education operating budgets have grown even as pension costs have grown. In other states, overall education funding has failed to increase at the same rate as retirement costs. While overall investment in education may appear to be increasing, on an inflation-adjusted basis, these states are actually spending fewer operating dollars today on K-12 education than in the recent past.

Some states pay all or most of retirement costs themselves, while others shift costs to districts. This can change the perception of how much funding has gone to public education. When costs are held entirely by the district, the consequences of pension liability are more acutely felt as local school boards struggle with increased annual payments. When the state simply fails to increase state general operating aid for education to districts to pay for growing obligations, the perception is that the state is failing to support education (even though they may be spending more than ever).

Sometimes school employees are included in the retirement plans as teachers, and sometimes employees are covered by separate state or local government plans. It is important to note that the figures above represent mainly teacher pensions and largely do not include administrators and other school support staff.

Why are pension systems underfunded?

Data from retirement system reports show that unfunded liabilities can be attributed to:

- Underperforming investments (50%)

- Changes to assumptions about mortality and workforce trends (20%)

- Interest on the debt (interest is growing faster than incoming contributions) (20%)

- Miscellaneous economic and actuarial factors (10%)

For any given state, the share of these factors causing unfunded liabilities might be a bit different. Some states have struggled with demographic shifts more than others; a few states have legacy pension debt from decades of not funding their plans in the 20th century. But nationally, pension debt is a mix of problems caused by retirement system trustees and state legislatures—the problems do not stem from gold-plated, ever-increasing teacher pension benefits.

There is certainly enough blame to go around. Instead of pointing fingers, we must look forward to how we can best keep teacher pension plans from further accumulating unfunded liabilities.

Equity implications of retirement benefits

As with most topics in education finance, there are significant equity implications of these growing costs of retirement benefits. States where the legislature directly pays for a portion of K-12 teacher retirement costs (typically called “non-employer contributions” or “on-behalf” contributions) are effectively providing a pension subsidy. These states include (but may not be limited to) Connecticut, Massachusetts, California, Texas, Illinois, and Michigan.

Currently, states like this distribute subsidies based on each district’s proportionate share of unfunded liabilities—but school districts with higher-paid, longer-tenured teachers carry a disproportionately larger share of the unfunded liabilities. The consequences of this are that:

- State shares of pension costs are regressive, and

- states are effectively subsidizing the compensation of teachers in wealthier districts at the expense of higher poverty districts with less experienced teachers (who likely have lower salaries and a lower likelihood of ever receiving their pension benefits).

Commonly, the most tenured and highly compensated teachers are concentrated in affluent districts. To the degree that a school district’s teacher compensation rates are higher-than-average, the state pension subsidies are exacerbating resource inequities. Districts with higher property wealth and incomes can also more easily handle increased pension costs, regardless of their share. Relatively small increases in property tax rates can raise significant resources, and these districts are often well below the same tax capacity as poorer districts that struggle to keep up with rising costs.

How do we fix the pension problem?

Two commonly proposed solutions do NOT address core problems. These include:

1. Just put more money in: Supplemental resources will be required to address unfunded liabilities, but adding more money to the system without addressing structural flaws or reviewing the (in)equity of state pension subsidies doesn’t build a path to a strong future.

2. Convert everyone to 401(k)/defined contribution plans: There are good ways to build public employee defined contribution (DC) plans that avoid the failings of typical corporate 401k plans. Offering the choice of DC plans can be a good way to support certain teachers/school employees who are not going to work their full career in a single state and/or work the 25+ years often needed for a decent pension. However, creating a DC plan for all new employees doesn’t do anything to address historic unfunded liabilities and fails to address any of the funding problems going forward. What's more, DC plans that are designed to save money typically don’t fully support retirement income security.

Four categories of solutions CAN help to reduce funding challenges. We consider each in turn below.

Solution 1: Transparency

States can implement reporting standards that reflect the effects of pension debt costs so hidden funding cuts can be addressed before they become untenable or damaging to teachers and students.

One possible approach: A general annual report tracking each dollar of K-12 spending, including shares going to retirement costs. Legislatures could determine the most appropriate measurement of education spending in their state, and require an annual report that compares this with the change in teacher retirement costs and whether they’re paid by the state and/or school districts. This is particularly important for states with funding formulas integrating local control of education resources, as any pension debt costs that get pushed down to districts can inhibit their ability to allocate those funds to improving educational outcomes and appropriate pay for educators.

States should also regularly review:

- Whether growing retirement costs for school districts are exacerbating education funding inequities.

- Whether state retirement payments (non-employer contributions) on-behalf of school districts, which are effectively a kind of pension subsidy, are inequitably distributed.

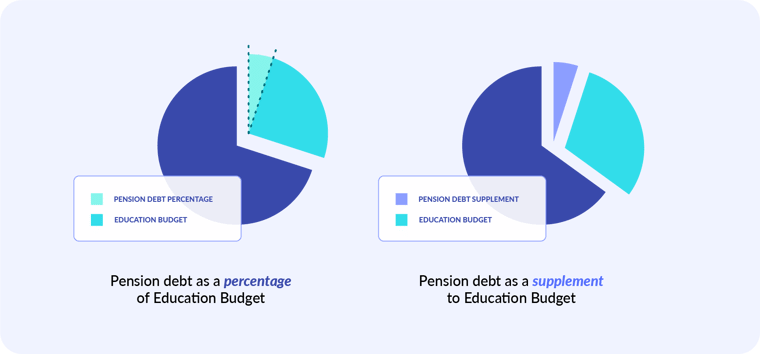

Solution 2: Use the State General Fund for Pension Debt Instead of Education Dollars

There is very little that school districts can do to manage pension plans or avoid the development of unfunded liabilities. It would be more appropriate for the state to pay for any costs of unfunded liabilities directly. A few specific approaches could be:

- Provide one-time, supplemental contributions to a teacher pension plan to pay down unfunded liabilities using budget surplus dollars and/or money from rainy day funds.

- Adopt a rule that school districts only need to pay for normal costs of retirement benefits. The “normal cost” is how much benefit each current employee in a pension plan has accrued each year. Districts would pay all of the costs required to cover current employees and not be responsible for covering the accumulated liabilities for existing retirees and liabilities accrued by failing to pay the full normal cost in prior years.

It’s important to note that state General Fund dollars are often fungible in terms of how they are allocated to different line-items, like education. This means that General Fund dollars can be budgeted with a high degree of flexibility, versus something like a targeted federal grant for public transportation infrastructure that must be used for a specific purpose. If the state absolves districts of accountability for unfunded liabilities, there must be some maintenance of effort protections in place to ensure that dedicated funds for education are not reduced to pay down pension liabilities. Without maintenance of effort provisions, "hidden" cuts to education budgets will become absolute cuts to education funding, which disproportionately hurts low-wealth districts due to their higher reliance on state aid (and lower contribution to pension debt). This strategy is only effective and equitable if the state budgets supplemental dollars for pension debt, rather than supplanting existing education budgets.

Figure 6. One recommendation to fix the pension problem is to use the state General Fund for pension debt, instead of education dollars. This strategy can be effective and equitable if the state budgets supplemental dollars for pension debt (right), rather than supplanting existing eduction budgets (left).

Solution 3: Improve Pension Funding Policies

All states should continuously work toward achieving a resilient funded status for their defined benefit plans. The specific challenges to solve and solutions for these challenges vary considerably from state-to-state. Each state has to look holistically at the current and potential future effects of pension debt costs and design targeted policy accordingly. While there are no one-size-fits-all solutions, some categories of change include:

- Adopt more realistic investment assumptions to avoid underperforming returns causing a growth in unfunded liabilities.

- Require state legislation that contribution rates are always at least covering the interest growth in unfunded liabilities. Typically, states calculate a “required contribution” that is an actuarially-defined value to meet their current and future liabilities. While not all states always pay their fully required contributions, the larger issue is that states control the method to calculate this contribution. That has allowed some states (Georgia, Maryland, Mississippi, and Nevada, to name a few) to pay their “required contribution,” but this value fails to cover interest on their debt. This sets up a runaway growth in pension liabilities, because the principal debt is never reduced. (This effect is just like paying less than the interest on your credit card debt while still making your minimum payment.)

- Develop two plans—one to pay off legacy unfunded liabilities and one to address future costs. While states should take care of the sins of the past directly, school districts should ensure future stability by being part of paying for pension benefits accrued from today forward.

Solution 4: Ensure Retirement Plans are Working for All

Many states have pension plans that only work for teachers with a 25+ year career in the same state. This means that even two decades in the classroom doesn’t provide a livable retirement. Some states have offered alternatives to pensions, but with very poor benefit values. Most states don’t give a choice of benefits to teachers or consider the dynamics of a more mobile 21st century workforce.

Ensuring retirement plans work for all doesn’t mean abandoning pension plans—states like South Dakota and Colorado have modern, adaptable pension designs for teachers. Strong pension plans have low vesting periods, robust benefit multipliers, flexible retirement eligibility, employer matching on refunds, and inflation protection built-in from the start.

There are bad ways to design defined contribution plans (also known as hybrid plans or “guaranteed return plans”). However, there are good examples of these models, such as those developed in Michigan, South Carolina, and Oregon. Strong defined contribution plans have adequate contributions that take into account whether or not members are enrolled in Social Security, have default investment plans so members don’t have to make choices, and offer annuities to “pensionize” accounts at retirement.

The Big Takeaways

The current public school pension system is fiscally unsustainable in many states. This contributes to depressed wages for teachers and school staff and presents a major threat to school budgets this decade, despite only benefiting a minority of teachers in the workforce today. There are practical solutions to 1) mitigate the negative fiscal impact to school budgets, 2) present diverse retirement benefit options that better serve all teachers, and 3) stabilize the financial future of public education, but these solutions require frank conversations and cooperation between district leaders, teachers, labor unions, and state legislatures.

This article is third in a series that reviews “10 Predictions for the Next 10 Years of Education Finance.” Read other topics in the series now:

- Teacher Compensation

- Declining Enrollment

- Pension Debt & Reform

- The Great Unbundling

- The Future of EdTech

- Reimagining K-12 Real Estate

- State Funding Formulas

- Investing in Early Childhood

- School Choice

- EdFinTech Climbs to New Heights

Special thanks to Anthony Randazzo for his contributions to this piece!

Contributing Author

Anthony Randazzo, Executive Director | Equable

Anthony works with stakeholders around the country to build collaborative approaches to complex political and financial problems. He was formerly managing director of the Pension Integrity Project and director of economic research at Reason Foundation. Anthony graduated from New York University with a multidisciplinary M.A. in behavioral political economy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jess Gartner is the founder and CEO of Allovue, where edtech meets fintech - #edfintech! Jason Becker is Allovue’s Chief Product Officer. Allovue was founded by educators, for educators. We create modern financial technology to give administrators the power to make every dollar work for every student. Anthony Randazzo is the Executive Director of Equable. Anthony works with stakeholders around the country to build collaborative approaches to complex political and financial problems.