Tax dollars are not necessarily allocated to students or even to schools in the neighborhoods of the taxpayer. Tax revenue is collected and distributed to schools throughout a district, and in a growing number of states, to districts throughout the state. Funding for public school districts primarily comes from state (i.e., sales tax, income tax) and local tax revenue (i.e., property tax), with less than 10% of funding coming from federal funds. The proportion of revenue a school receives from local and state funding differs across each state and depends upon: 1) whether local government distributes dollars directly to the school system or sends funds back to the state for distribution, 2) the state funding formula, and 3) local municipal revenue sources and budgetary allocations to education. Regardless of the distribution process, the amount of tax dollars that are allocated to schools depends on how the local government generates revenue.

1. How does local government generate revenue?

2. How does the state allocate funds to school districts?

3. Where do your state and local tax dollars go?

1. How does local government generate revenue?

Local revenue is generated by a combination of property tax, sales tax, and income tax, and is a major funding source for many school districts across the country.

Terms to know:

- Property Tax: A tariff assessed to the value of real estate levied by the governing authority and paid by the owner of the property.

- Millage Rates: The tax rate used to calculate the local property tax amount. The rate represents the amount per every $1,000 of a property’s assessed value. For example, “one mill” would equal $1 in tax for every $1,000 in assessed-value. The sum total of all the millage rates equals the property tax rate for a particular locale.

- Assessed Value: The dollar value assigned to a property.

- Tax Abatements: A reduction of taxes granted by a government to encourage economic development. The most common type is a property tax abatement granted to a business as an incentive to come to a city or expand existing operations within the city.

Property Tax

Property taxes are subject to assessed value calculations, millage rates, and tax policies of personal- or privately-owned properties. Though this primarily includes residences and businesses, it sometimes includes vehicles and other forms of personal property. Public- or government-owned buildings, structures, and parks are generally excluded from property tax calculations. Property taxes can vary state-to-state, city-to-city, and those variances can create inequities based largely on the affluence of a zip code.

The amount of revenue generated by property taxes also depends on the municipality’s ability to collect those taxes. If a city is only able to collect a portion of owed property taxes from businesses and individuals, the reduced revenue will impact the amount of funds available to allocate to school districts.

How property taxes impact school district revenues

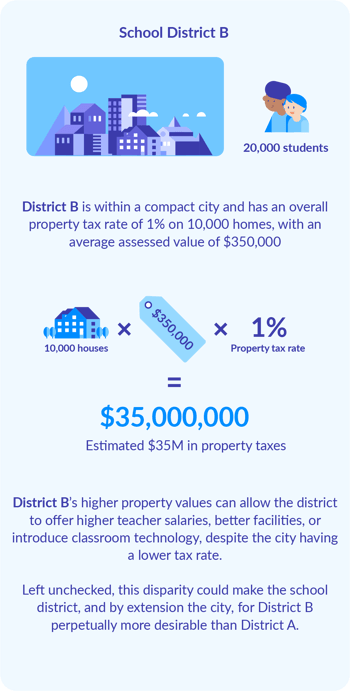

School District A and School District B are located in neighboring cities in the same state.

Each district enrolls 20,000 students and each receives 100% of the revenue generated from the property taxes levied.

Tax Abatements

Many cities offer tax abatements to prospective employers in order to generate new business and employment opportunities for its residents. New business properties with granted tax abatements often go untaxed for a specified number of years, even decades, despite having an assessed value and stated millage rates. These incentives allow new businesses to build and thrive within local communities without directly contributing to the communities’ assessed value, thus lowering the overall tax-base, expected revenue, and public benefits that would have come from the additional revenue.

Bonds

Some districts generate additional local revenue using a bond/levy. School bonds are essentially loans that allow the district to fund large capital projects like building new schools or renovating older school buildings. These low-risk bonds are issued and sold on the bond market and can provide tax-free gains to the purchaser. The school district, in return, levies a higher millage rate on the public in the form of temporarily higher taxes to pay back the value and interest on the bonds. The possibility of higher taxes means bonds are usually voted on by the local public before they can be issued.

2. How does the state allocate funds to school districts?

Some states develop funding formulas designed to fill the gap between what can be raised locally and the basic level of funding required for schools. However, these formulas are often complex, impacted by political influences, and are generally not nuanced enough to effectively support every local context.

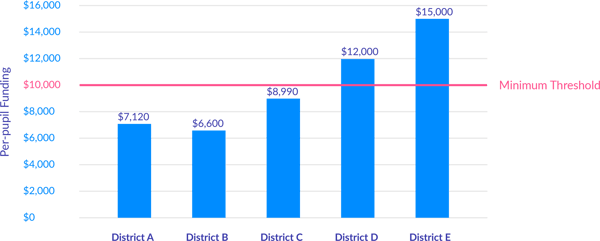

To identify potential gaps in funding, most states use forecasted data sets to project how much a local municipality could generate in funds. The state distributes funds based on these projections with the goal of leveling the playing field for all students within that state. However, if the state estimates higher or lower property tax revenue than what is likely for a particular locale, it could adversely affect the district’s funding potential. A state that only ensures that each district reaches the minimum threshold for education may do well to reduce local funding gaps, but will not effectively eliminate them.

Example: A state has five districts for which it provides supplemental funding. This state uses a simple funding formula that identifies $10,000 per-pupil as the minimum threshold needed to operate a district. District A can only raise $7,120 locally; District B, $6,600 locally; District C, $8,990; while Districts D and E have both raised beyond the minimum threshold at $12,000 and $15,000, respectively. A state funding formula that focuses on bringing districts A, B, and C up to the minimum threshold will help narrow the gaps across the five districts, but still may not be equitable. Additionally, schools A, B, and C will still be funded at significantly lower levels when compared to Districts D and E. Equality does not create equity. $10,000 at a district with a higher-cost-to-serve student population may not go as far as $10,000 at a district with a lower-cost-to-serve student population.

The planned and collected revenues, including revenue earmarked for schools, are budgeted to the local education agency through the local government’s budget adoption process. The process typically includes community comment and voting by elected officials at budget hearings. Once the budget is completed and approved, the dollars are sent to the local education agency, usually on an annual or biannual timeframe (states similarly allocate their budgeted dollars to school districts annually or biannually), for distribution to schools.

Once dollars are allocated to a school district, the district is responsible for constructing its own budget and having its budget approved by a school board or district council. This budget details where dollars will go within the school system, including central office departments, schools, facilities, and capital projects.

3. Where do your state and local tax dollars go?

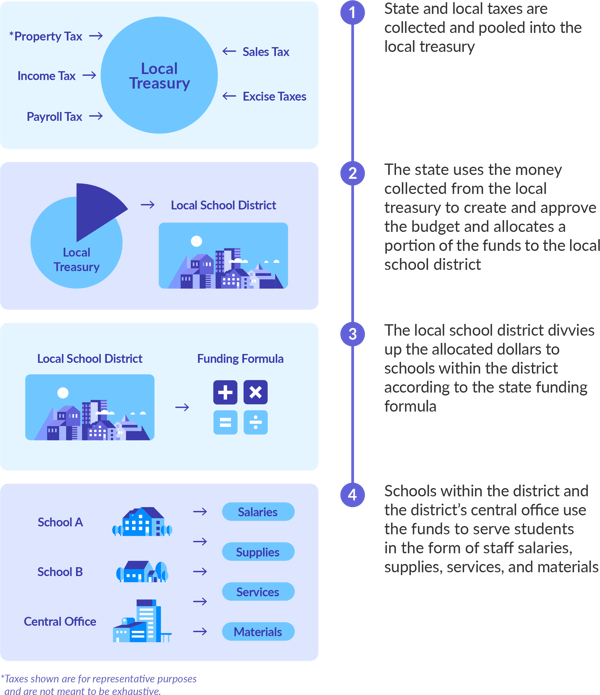

The infographic below can help taxpayers better understand the ‘why’ behind the pathway of the dollar from their pockets into student’s backpacks.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Allovue works with districts and state departments of education across the country to allocate, budget, and manage spending. Allovue's software suite integrates seamlessly with existing accounting systems to make sure every dollar works for every student. Allovue also provides additional services such as chart of accounts and funding formula revisions.